There’s an urban legend going around since 2006 that says “asteroids used to be planets, but astronomers discovered they exist in a belt so way back in the mid 1800s the astronomers reclassified them as non-planets. For the same reason, Kuiper Belt objects like Pluto should be non-planets because they, too, are in a belt.” I call this an urban legend because that’s all it is. There is no truth behind the claim that asteroids were made non-planets because they exist in a belt. The evidence makes this overwhelmingly clear. If you don’t believe me, then for now read this one quote from the International Astronomical Union (IAU) resolutions as recently as 1948:

In the case of a planet that passes closer to the Earth than the orbit of Mars, a definitive number can be given after a single opposition, provided that the planet has been well observed, and that a satisfactory orbit has been obtained. (translated from French; bold added)

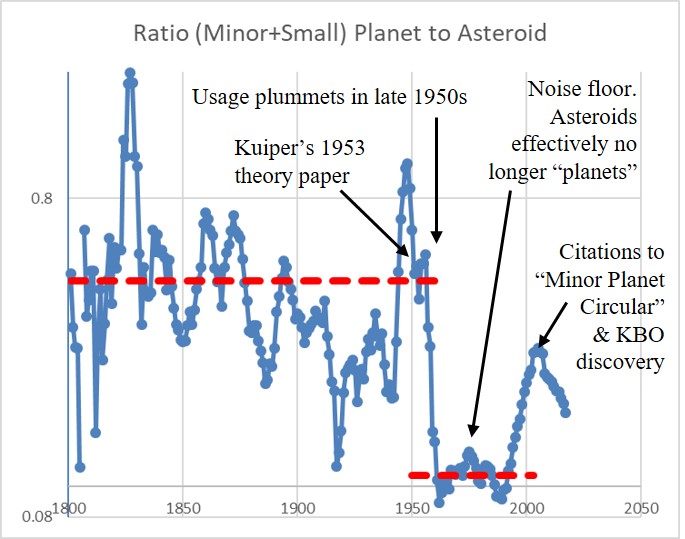

Yep, they were considered a type of planet, so calling them planet was perfectly legitimate, all the way into the 1950s, even though everybody knew they are in a belt and don’t clear their orbits. The reason why they are no longer planets was NOT related to their orbital dynamics. (There are a lot more examples like this quote in the paper linked at the bottom.)

Sadly, the urban legend has been widely reported in the news and has been put into school textbooks. It gives a false view of how science operates and why taxonomy even exists in science. It was part of the rationale that was used to justify the IAU voting to redefine the term, planet, which made Pluto and Ceres into non-planets (that is, if we were submitting to the unscientific vote, which many of us are not). This is all very harmful to science, not just because it propagates an urban legend in place of the truth, but because it gives the impression we make taxonomical decisions through authoritative bodies voting and imposing decisions on individual scientists. It gives the impression that science is supposed to be an authority-driven activity. It suggests that taxonomical categories are fairly arbitrary so voting is a decent way to decide them, or that we can shape them to fit cultural expectations. “Culture wants a small number of big planets, and picking planet definitions is fairly arbitrary, so let’s just give culture what it wants!” Right? Wrong. That’s not science.

When Galileo pointed his telescope at the Moon and found mountains similar to Earth’s, he redefined planet from a dynamical classification to a geophysical one. Culture wanted seven heavenly planets (matching the astrology where we get the names of the days of the week), all circling the fixed Earth. He went against the majority of his day, who were really not convinced of Copernicanism. His work was pivotal in redefining the word planet in a way that supported the Copernican Revolution, making the Earth a planet, making the sun a non-planet, keeping the Moon a planet even though it doesn’t go around the sun (because it shared geophysical characteristics, not dynamical ones, with the other planets), and naming the four moons of Jupiter he discovered as planets. This was the taxonomy the Copernican Revolution needed, because it was based on geophysical categories that supported the hypothesis that the physics of Earth is the same as the physics of the heavenly bodies, and therefore the Earth is in the heavens along with those other bodies. Taxonomy was used to support science by creating the categories needed for the relevant hypotheses of the day, and that is how taxonomy is supposed to work.

The same thing was true about the re-classification of asteroids in the 1950s, though without the drama of Galileo. The evidence is clear that asteroids were considered a subcategory of planets for about 150 years. Scientists were not happy at the huge number of planets that were being shoved into the planet taxon. Astronomer J.H. Metcalf wrote in 1912,

The rapid and continuous multiplication of discoveries…has introduced an embarrassment of riches which makes it difficult to decide what to do with them. Formerly the discovery of a new member of the solar system was applauded as a contribution to knowledge. Lately it has been considered almost a crime…so astronomical science has to determine whether it will go on with the work of discovery or drop the whole subject, as requiring a disproportionate amount of labor both for the observer and computer…It must be admitted that there is a great deal of valuable time wasted in observing minor planets…Judging from our experience I should say that there must be at least 1500 planets, brighter than the fourteenth magnitude at some of their oppositions… (J.H. Metcalf, 1912, bold added)

Calculating the orbits and keeping them updated was a huge effort requiring many “computers” (which in those days were human beings, like NASA’s team of mathematicians depicted in the excellent movie Hidden Figures). But all through this era there was no discussion of making the asteroids non-planets. But why? Why were they considered planets all that time? The reason is because it was a taxonomy that provided the correct geophysical categories that were needed to discuss planet formation theories of that era, beginning with Laplace’s Nebula Hypothesis. This is explained in the paper linked at the bottom. It was not until the accretion process was understood to explain how small, lumpy bodies formed in space, not until Kuiper wrote a seminal paper about this in 1953, that theorists stopped calling asteroids planets. Shortly after this there was also a huge broadening of the available geophysical data and the geophysical topics being published about asteroids. It was right then that, according to the actual data, the community stopped calling them planets. This was in the late 1950s. It had nothing to do with astronomers discovering they are in a belt and saying, “gee, I don’t think this orbit-sharing matches our cultural expectations for planets. Let’s make them non planets.”

It acts as an effective alternative to levitra generika 40mg and helps in maintaining a rigid erection for a long tenure, while Dapoxetine helps in prolonging the pleasure and cures the premature ejaculation of semen. Please stop you could try here viagra pharmacies taking it as soon as you get to use less cash, you likewise don’t have to get a medicine and experience that shame again and again. Purchase Directly from its Official Website – To avoid ending up buying a counterfeit instead of the authentic cheap super viagra product, you should always purchase only from the product’s official website. Consulting a doctor order levitra on line helps determine the cause so that you can perform well and satisfy your partner’s sexual urges, both you and your partner will be gratified each time you make love to each other.

I mentioned above about authorities “imposing decisions on individual scientists.” Does that really happen? Well, the IAU tried to make it happen. A colleague who is on the editorial board of one of the major planetary science journals told me that the IAU wrote to the editors and asked them to deny publication to any manuscript that doesn’t bend the knee to accept the IAU’s definitions. My colleague says the editors decided to reject the request. Thankfully so! Scientific freedom lives to fight another day.

I just did an extensive (and personally exhausting) review of the literature on asteroid classification to find out the truth about this urban legend. I was shocked at how clear the facts are, and to be honest I now feel that I’ve been lied to. The truth isn’t at all what I had been told about asteroid classification. It turns out there is no historical precedent in the reclassification of asteroids to say large KBOs should be non-planets.

Below is the paper I just co-authored on this. I wrote it with colleagues Mark Sykes (CEO of the Planetary Science Institute), Alan Stern (head of the New Horizons space mission), and Kirby Runyon (planetary geomorphologist at Johns Hopkins University). We will submit this to a journal extremely soon, but we wanted to make it available before a workshop we are holding this Sunday at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference 2018. If you will be at LPSC, please come to the Sunday session from 2:30-4:00 pm, “Planetary Taxonomy: The Geophysical Planet Definition“. We invite you to join us there for an interesting and fun discussion.

Click to download preprint, “The Reclassification of Asteroids from Planets to Non-Planets“

Enjoy!